Peter Green: Looking back through the smoky prism of time

On the 29th September, we published a revised 4th edition of Martin Celmins' definitive biography of guitar legend Peter Green. Martin has kindly agreed to write several blog posts for us, including 'Peter Green - Ten post-Mac tracks' and 'Mythic Munich: Additional Perspectives'.

In this blog, Martin provides new information about recordings and events covered in previous editions of the biography.

The End Of The Game, Albatross, Man Of The World, Then Play On & Blues Jam At Chess

This blog highlights contrasting perspectives from Peter Green and Mick Fleetwood about The End Of The Game album. It then features extracts from interviews with Peter from different eras, referencing Albatross, Man Of The World, Then Play On and Blues Jam At Chess.

Not only did the two bandmates’ perspectives differ, but their own views and recollections also changed markedly over time. So, deciding which scenario was the likeliest back then sometimes is down to guesswork.

Peter Green Founder of Fleetwood Mac devotes a chapter to Peter Green's The End Of The Game project, detailing the June-July 1970 De Lane Lea Studios sessions for Peter’s first solo album after leaving Mac.

Much that is new has come to light thanks to invaluable input from Nick Buck, keyboardist on the sessions. The edited jams selected for The End of the Game album took place towards the end of July. Zoot Money on piano joined Peter, Nick on Hammond organ, bassist Alex Dmochowski and drummer Godfrey MacLean on the penultimate July 25th into-the-night session.

For the first edition of my book Peter Green – The Biography, Zoot was the main source of information about the recording: “So I arrived at the studio at ten in the evening and just played for three or four hours. There was no structure, just an exchange of ideas, and when we finished I put on my coat and said ‘See you on vinyl.’ and left.” Zoot played on two of the album’s six tracks – 'Descending Scale' and 'Hidden Depth'.

Photographer Bruno Ducourant was also there earlier on July 25th, and remembers Peter being focused and enjoying himself. And the fact that he had asked guitarists John Moorshead and then Danny Kirwan to sit in on that same day does suggest that it might have been a somewhat different record if some of their playing had been included.

What’s more, when work on the album began in early June, Peter seemingly had an Afro-Rock percussion-led project in mind judging by the first group of musicians – and the last as it turned out – which he invited along to jam, Ginger Johnson’s African Drummers.

When released in November 1970, the album was an often wah-wah guitar-led instrumental and it received a mixed reaction. Sales were disappointing. And yet, since then some critics have come to regard it as a free-form improvisational masterpiece.

Not only have critics changed their opinions over time, so too have Peter Green and Mick Fleetwood.

For instance, in his autobiographies Fleetwood – My Life and Adventures with Fleetwood Mac (1990) and Play On (2014), he expressed rather different views about The End Of The Game.

In 1990 he recalled that the Kiln House Fleetwood Mac line-up was saddened and mystified when they first listened to the album’s weaving, meandering jams. The drummer was left wondering just what had gone wrong with his old friend. And yet in 2014 he said that on first hearing he felt bewildered and hurt.

Why hurt? Because before leaving, Mac’s leader had given him the impression that he was going to head in a radically new direction; but then on hearing the album the drummer thought that - different though it undoubtedly was - its free-form style was not that far from what Mac was playing shortly before he left.

He now felt that the band would have been quite willing to do the tracks on the album and he didn’t understand why their leader hadn’t tried to do that.

This is a perplexing viewpoint in that the tracks on the album were, of course, the outcome of spontaneous jamming between the musicians involved: the jamming bedrock often was laid down by drummer Godfrey MacLean and bassist Alex Dmochowski whose playing styles are quite different to those of Mick Fleetwood and John McVie.

Peter has since said that he didn’t feel that Mac’s hearts were in jamming and free form and, as Dennis Keane pointed out in the first edition, the crucial editing of the Madge session was all done by the leader.

This assertion about the band not really being into free-form is reinforced by the drummer himself in 1990’s Fleetwood when he recalls the six weeks in February and March 1971 when Peter replaced departed Jeremy Spencer on Mac’s US tour.

In 1990, the drummer remembered the set consisting of 'Black Magic Woman' and ninety minutes of free-form jamming which, he wrote, left the band bored stiff, even though their ex-leader’s playing was brilliant. Scared stiff was how John McVie remembered the band sometimes felt before going on stage, not knowing what they were going to play.

But talking to the NME June 16 1973 Mick recalled: “When Jeremy left, Pete played the American tour with us, it did us a lot of good. Pete didn’t want to play any set numbers so we’d just jam. Pete would force us into whatever style he wanted us to play and it jolted us out of our music. A whole set of jamming is quite difficult; with an audience there you’ve got to be entertaining and not simply self-indulgent.”

In 1998 Peter told 20th Century Guitar Magazine: “I did not insist on jamming it just happened.”

A bootleg tape of the first gig with Peter at the Swing Auditorium San Bernardino on February 19th has a set including numbers like Danny Kirwan’s 'Station Man', 'Tell Me All The Things You Do', 'Dragonfly', and Christine McVie’s rendition of 'I’d Rather Go Blind' and 'Get Like You Used To Be', plus the band’s 'Purple Dancer'.. On 'Tell Me All The Things You Do' in places Mac’s calling card twin-guitars are back, and some nice Greeny phrases are there in the Etta James classic. The set ends with a percussion-driven jam.

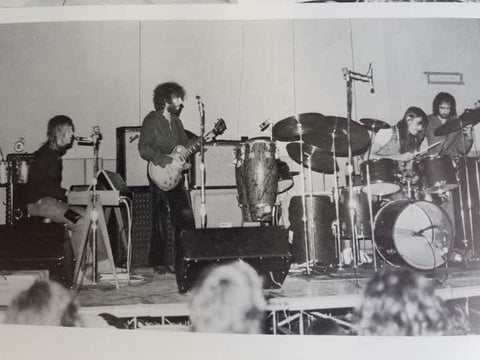

Below, are photos taken on that tour at three gigs. One at Eastown Theatre, Detroit, 12 March, shows Peter singing. The song in question may have been ‘Black Magic Woman’ or perhaps a rock’n’roll finale to the show.

Fillmore East Backstage Feb 26/27 1971 Credit: Marian Tortorella

Eastown Theatre Detroit March 12 1971 Credit: Diane Cornelius

Eastown Theatre Detroit March 12 1971 Credit: Diane Cornelius

Feb/March 1971 Credit: Rick Gage

Feb/March 1971 Credit: Rick Gage

Interestingly, just five days before Jeremy Spencer went awol in LA, journalist Rick McGrath interviewed him and Mick Fleetwood in Vancouver’s Bayshore Hotel.

The February 10 concert was at the start of the Kiln House tour at Vancouver’s Gardens Auditorium, and recordings of which are featured on the Preaching The Blues and Madison Blues Mac CDs.

Ironically, Jeremy is on top form and the interplay between him and Danny is especially impressive on the extended intro to Mac’s high energy electric cover of Big Joe Turner’s Honey Hush.

At one point Rick McGrath referenced The End Of The Game. The whole interview was later published in local news and entertainment weekly paper The Georgia Straight (18.4.71). Here is the transcript of The End Of The Game extract of the interview:

RM: Peter’s new album, have you heard it?

MF: It’s a jam.

RM: Yeah, the whole thing.

MF: It’s not a bad jam, though.

RM: Yeah, but jams are limited. You have to have more than one imagination working.

MF: They’re not sparking off properly.

RM: There’s a couple of cuts that are highly suggestive, but there’s a few that don’t do anything for me.

JS: As far as Peter is concerned, the guitar playing is good, and some of the cuts sound like wild animals.

RM: Yeah, especially the first cut. And it’s done with a wah-wah.

MF: The whole thing is wah-wah isn’t it?

JS: Yeah, it seems that wah-wahs aren’t very popular these days.

MF: Well, Jimi Hendrix played it so well that I thought people were scared to use it after him because he played it the best. If you’re not going to do anything different, what’s the point?

So, over some forty-three years, the drummer’s perspective on the album shifted from initial qualified praise …. ‘It’s not a bad jam, though … They’re not sparking off properly’ (1971) …. to sadness about the guitarist’s playing and his misjudged free-form project (1990) …. to feeling hurt about a missed opportunity for the original band to stay together by following their leader in his new musical direction and playing on a free-form album (2014).

The guitarist’s own views about the album have also changed a great deal.

In 1994 for the first edition of Peter Green – The Biography he recalled: “There wasn’t enough there. When I was editing it, I found out that there wasn’t enough to make up a record. It was only free-form.”

Subsequently, he told journalist Cliff Jones [The Guitar Magazine January 1997] : "End Of The Game” helped a little. It taught me what was and what wasn’t possible. I made it as an experiment because I felt restricted. I’m still restricted and I can’t learn fast enough to say what I have inside .. but I’m learning again. That was the problem in the beginning, I couldn’t play the things I heard in my head. It makes you want to give up sometimes. I thought maybe I could get closer to it by doing it that way. I don’t think it worked too well.”

But in 1981 when interviewed by Serbian journalist, Dragan Kremer, for the May 1981 issue of Yugoslavian rock magazine Dzuboks [Jukebox - this insightful interview was recently translated by Misa Drezgic for his Peter Green Blues Society Facebook group] when asked for his opinion ten years after The End Of The Game’s release, the guitarist said: “I love it! It’s a superb album. The jam was incredible, the bass player [Alex Dmochowski] was excellent, you know. Recordings were great … it was recorded in England.”

Surprisingly, he also remarked that the album to him did not seem that different compared to what came before, and when asked again if he was pleased with it he said: ”Yes, pretty much. Of all albums I have recorded, I am most pleased with The End Of The Game. But, had I kept recording, I doubt that I would have made more stuff like that. [The] Album really wasn’t popular – it was a genuine underground record. There’s not many people who love it … there was no singing and all that. But I love it. Outstanding LP.”

Peter Green – Founder of Fleetwood Mac also devotes a chapter to the guitarist’s gigging during that summer 1970 at free festivals and charity events. Sometimes this was as a duo with Nick Buck on electric piano but more often it was as Peter Green & Friends with more musicians joining them.

In 1981 Dragan Kremer asked him if he didn’t want to be recognised as Peter Green at those small gigs : “Yes … it didn’t matter to me, it didn’t mean anything to me. I just didn’t care. And after a while, I made sure that no one was coming because of me, that they didn’t recognise me anymore. I saw that was possible after all.”

Asked about who played with him he said: "Alex Dmochowsky on bass. Nick Buck on electric piano. And everyone else who wanted to play, you know. That was unofficial, more like jamming.”

Guitar Player November 1994 features a wide-ranging interview with Peter by Ben Fisher which references his summer 1970 free festivals and gigs, free-form era. “…. I played a tour with just myself and Nick Buck an American guy who played electric piano. That’s when I was playing at my best. When you’re getting paid there’s too much pressure”

Some of his views about 'Albatross' and 'Man Of The World' also changed over time.

In 1981 Kremer asked if Mac’s singles were a means of exploring something new: “Yes, singles were different since they originated at the beginning of the recording process. I would say, ‘This thing ‘Albatross’, will be on the album’ but no! They would nag and nag, and then release it as a single! ‘Man Of The World’ was a track for Then Play On – but they would say this and this has to be a follow-up and then it would end up as a single. But I didn’t want to make new versions of ‘Albatross’. And then, when we finished Then Play On, the studio jams had to be added afterwards. Nevertheless it is a very good album. We loved it, we had a lot of good will for it but it did not turn out so great.”

However, Peter Green Founder of Fleetwood Mac references an interview in 1969 with Rick Sanders for Rolling Stone (14.6.1969) in which Peter said: “What I am after is atmosphere ….well… and I’ve had ideas in me for a long time that are starting to really come out now …stuff like Albatross. When we recorded that I knew it had to be a single, though the others needed a bit of persuading.”

His serene composition was one of seven tracks taped on October 6th 1968: four were Danny Kirwan songs which would be re-recorded or re-mixed for Then Play On: 'Coming Your Way', 'One Sunny Day', 'Like Crying' and 'Without You' plus 'Something Inside Of Me' and ‘Jigsaw Puzzle Blues’. 'Albatross' may have had more work done on it during the week Oct 14 -18th.

Then, interestingly, Rave magazine’s Kate Joseph interviewed the band after their October 28th 1968 Shakespeare Hotel gig in Woolwich.

She reported that they were halfway through the new album which would be very different. Peter made no specific mention of 'Albatross' as the next single. But ‘The Albatross’ was mentioned in his November Beat Instrumental column and compared to classics from his hero Hank Marvin – such as 'Apache' and 'F.B.I.' The single was released on November 22nd.

An interesting point arising from the 1981 interview is that when the guitarist said ‘And then, when we finished Then Play On, the studio jams had to be added afterwards’ did he mean that the ‘Madge’ studio jams were an afterthought and solution to fill the gap originally intended for 'Albatross' and 'Man Of The World'?

Mick Fleetwood, interviewed by David Fricke for the 2013 remastered Then Play On liner notes seemed to suggest that the Madge jams were more intrinsic to plans for the album: “Before that [i.e. experiencing and hearing West Coast influences and bands like the Grateful Dead, The Byrds, and Creedence Clearwater Revival] our version of jamming was Peter saying, ‘I’ve got some ideas. I’ll come ‘round to your living room. Let’s get a snare drum and do some stuff before we go into the studio.’ But for Then Play On we allocated time, lots of it, specifically to jam. Those pieces on the album – the ensemble rave-ups ‘Fighting for Madge’ and ‘Searching for Madge’ were off the top of even Peter’s head.”

Christopher Hjort’s Strange Brew reports that those two ‘ensemble rave-ups’ and the serene edited jam ‘Underway’ were taped in one day – June 8 1969 – plus an eerily atmospheric instrumental duet by Danny and Peter – titled ‘Danny’s Instrumental’ on the tape box.

Sadly, this Kirwan gem was not released back then. But the June 8 recording (and unabridged ‘Madge’ jams) features on The Vaudeville Years double CD and is given the title ‘The Madge Sessions – 2’. It is on YouTube as Fleetwood Mac – The Madge Session , no 2.

Lastly, the 1981 Kremer interview reveals another interesting shift relating to that well-known topic - ‘can white boys truly play the blues?’ - a perspective which differs from that which the guitarist expressed in the first edition of Peter Green – The Biography.

In 1994, the author asked Peter about the Blues Jam At Chess session – produced by Mike Vernon and Marshall Chess. This resulted in a brilliant double-album blues timepiece on Blue Horizon first released in late 1969; and a soon-to-be-published photographic book Fleetwood Mac in Chicago: The Legendary Chess Blues Session, January 4 1969 co-authored by session photographer Jeff Lowenthal and Robert Schaffner, The book features forewords by Mike Vernon and Marshall Chess, a new interview with Buddy Guy, and includes recollections from Kim Simmonds, Aynsley Dunbar and Martin Barre.

On the session Mac played with Chicago blues greats Willie Dixon, Buddy Guy, Otis Spann, Walter ‘Shakey’ Horton, J.T. Brown, David ‘Honeyboy’ Edwards and S.P. Leary.

Looking back in 1994 Peter’s perspective about the session was surprising: “Those black guys knew that you can’t get the hang of it -they knew that whatever a white guy tries to do is not gonna be the blues of coloured people. It’s a pose all along. In Chicago that time, I played too forcefully – too much and too loud – because my experience in life didn’t match up to theirs. Perhaps white folks should’ve left those coloured tunes alone and stuck to singing hymns! At those Chess sessions my voice sounds like I’ve been drinking ginger beer, or am singing down the toilet.”

Asked by Kremer in 1981 how the session went, he said: ”There were no special preparations. We just came there and played with them, depending on who happened to be there. Buddy Guy was there, Willie Dixon too…… But I wasn’t quite pleased – it could have been better….”

But importantly, in that 1981 interview Peter identified as Jewish, not white, when Kremer asked him: “Were you, and others like you, obsessed with the idea to live the blues, trying to prove that white man has a right to his blues?”

Peter replied: “No we weren’t. And, actually, I am not white, I am Jewish. That’s why I don’t consider myself so-called “White Man” – that would rather refer to an Englishman. I also come from an ethnic group that has suffered a lot in its history, you know. There has to be a reason for the blues. Slavery, for instance. Of course, not in every particular case, but white man was – because of slavery – the reason for black man’s blues.”

Then Kremer asked: “Playing the blues, how did you feel in comparison to original performers? Don’t you think you were imitating them?” He replied: “No, no! I’d rather say I agreed with them. At that time doors were opening for that kind of music and I considered it mine. After all, we all play that same basic rhythm.”

Kremer also asked if there is something analogous to the blues to be found in Jewish music and, if so, why doesn’t he play it: “I think that Jewish music has a lot in common with Afro-American music, but that was usually a rigid reserved folk music. It seems to me that my song “Supernatural” has that Jewish feeling, that specific sort of feelings, you know.”

So, for both Peter Green and Mick Fleetwood it would appear that, over time, recollections about important events can change and sometimes can become somewhat negative and downcast.

That being so, the natural conclusion is that those opinions expressed soonest after the event come closest to the truth of the matter.

Dear Mr Celimins,

Thank you for deciding to make a more complete biography of Peter Allen Greenbaum. I look forward to reading it as soon as my copy arrives later this month. In anticpation of this: Kudos to you, Sir!!

Thank you! And for the photos too. The photo from Fillmore East 2/71 tells us Peter was back for about a month between Jeremy leaving and Welch joining in April. I guess the Swing Auditorium tape is the only evidence.

Very interesting, and thank you for the mention of our book, Both our books are released on the same day in the U.S. Really looking forward to the new edition of Martin’s excellent book!